So I was right: there was as much confusion as I thought there would be yesterday. Got up early, walked into CHUK. Hospital is made up of what are essentially one story barracks. The grounds are meticulously maintained by a hive of workers that are constantly grooming and cleaning.

Every patient is helped by a "caretaker," a family member that stays with the patient, cleans them, makes food for them, everything. What is amazing is how all the caretakers will take care of not only their family, but also the person in the bed beside the patient they are here to see. But not only that, the caretaker must go and buy many of the supplies, like exam gloves, for their family member. You learn not to waste even the littlest things very quickly, when you realize how it really is coming out of the pocket of the patient and their family. Caretakers also are responsible for getting tests done. The machine that does a test known as a "complete blood count," a test we get in the USA at least once a day, is not functioning. So to get this test done, a patient's caregiver must get the blood and the proper paperwork, get on a bus or the ever-present motorcycle taxi, and then drive across town to another hospital with a working machine and deliver the sample. Then they must get the results and come back to CHUK. This process can break down in any of a number of places, literally.

The emergency room is mass chaos. One, its not really an emergency room: it's a hive of wards, each with about 20 patients crammed into a space the size of my living room. Patients are being moved constantly. Work ups are non-existent. Nothing is acute, even traumatic injuries have been there for days before they are seen by surgeons. GPs run the ED, and they are overwhelmed with no resources. Most patients are first seen at a district hospital before being sent to Kigali, so there is usually a delay of days to weeks before they arrive here.

You constantly are saying to yourself, he sat around for how long with that? How has he not been to the OR yet? For example, today my Rwandan-speaking colleague was stopped by a patient about an iv that was backing up. As he was talking to this guy, I noticed clear fluid dripping from his right ear--he had been in a mototaxi accident, and had had cerebrospinal fluid dripping from a basilar skull fracture for days ("for the first two days, blood was coming out, now this fluid is leaking out." Unbelievable.) No head CT. No neurosurgeon consult.

Things seen yesterday: open dislocated thumb joint from two weeks ago that now was draining massive amounts of pus. A 90 year old lady with a displaced hip fracture who comes in with huge decubitus ulcers. 75% total body surface area burns. Dead foot needing amputation. A huge tumor of the liver that was able to be diagnosed by palpating of the abdomen alone.

Today: guy after an accident two days ago with this cervical spine x-ray:

That's a C4 on C5 subluxation with complete spinal cord transection. Couldn't move anything below the neck except his shoulders. More dead feet. An eight month old boy with 50% TBSA burns that were three months old. Chronic malaria infection resulting in a spleen that fills half the abdomen.

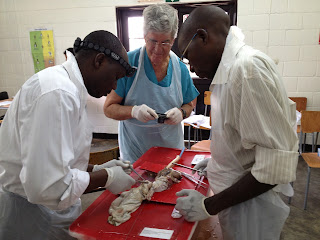

This all can create a sense of hopelessness in the situation. What can I do in the face of this burden of disease that has remained untreated for so long? The Americans here are not trying to teach diagnosis, or better surgical skills; these guys already have those things. They can do more in the operating room with much less than we can. The Americans are trying to implement a culture change, an attitude that says it is not acceptable for these patients to sit around for so long. Organization. Breaking down the roadblocks that prevent care from occurring.

Let's see if this change can be done on a faster time scale than geologic.